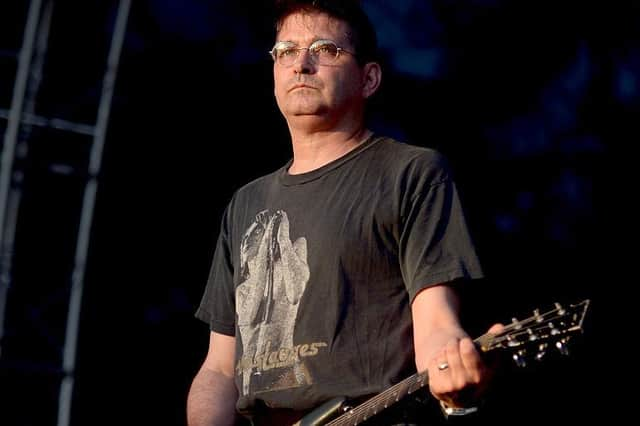

Scotsman Obituaries: Steve Albini, studio engineer who produced albums with some of rock’s biggest names

Steve Albini, who has died of a heart attack, aged 61, was a hallowed if controversial figure in the alternative rock realm, admired for his uncompromising fidelity to DIY punk culture, whether making harsh noise rock in his bands Big Black and Shellac or capturing the raw power and spontaneity of artists such as alt.rock titans Nirvana, Pixies, The Stooges and PJ Harvey in the studio.

Although associated with the heavier end of the musical spectrum, he also produced albums for the diverse likes of Pulp frontman Jarvis Cocker, power pop legends Cheap Trick and B-52’s frontman Fred Schneider, while Jimmy Page and Robert Plant engaged his unvarnished services on their 1998 Walking Into Clarksdale album.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlbini was mythical yet accessible, personally manning the landline at his Electric Audio studio in Chicago. He refused to act as an artistic gatekeeper, eschewed the term “producer” for its associations with creative decision-making.

Instead, he considered himself a studio engineer, hired to record quickly to a high standard on analogue equipment, capturing the performance in the room via astute placement of microphones.

There was no fix it in the mix with Albini, who charged a reasonable day rate for his services rather than claim royalties and, as such, remained affordable to smaller names on tight budgets. He may have happily passed up the royalty windfall from working on Nirvana’s In Utero but he made a fair bit of pocket money from his card-playing sideline, winning two World Series of Poker bracelets.

Albini was reckoned to have produced several thousand recordings over the past 40 years, including a brief stint in suburban Edinburgh in January 1990, when he recorded The Breeders’ classic debut album Pod in Palladium Studios, located in unassuming Buckstone Gardens.

Palladium was a residential studio with bedrooms upstairs – the band recalled recording and even visiting the local pubs in their pyjamas.

The studio was booked for two weeks but, with typical Albini efficiency, the album was done and dusted in one week and came in under budget.

He also worked with Glasgow band Mogwai on My Father, My King, a 20-minute instrumental reworking of a Jewish hymn, self-styled as "two parts serenity and one part death metal” and, more recently, with Dundonian outfit Spare Snare on their 2023 album The Brutal.

Albini was happy to spread the love and knowledge – at Spare Snare’s invitation, he hosted a Scottish Engineers’ Workshop in Blantyre’s Chem19 Studios.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn rock’n’roll parlance, Steve Albini was for real. He was something of a blunt instrument, dismissive of pop and dance music but consistent in his application of punk principles, speaking out against the innately exploitative nature of the music industry and suspicious of corporate machinery, including contracts. “I don’t sign things,” he once said.

He was not a fan of music festivals but made an exception for the Mogwai-curated All Tomorrow’s Parties in 2001 and played many subsequent editions of the boutique festival with Shellac, his third and longest-lasting band, formed in the early Nineties with Bob Weston and Todd Trainer. At the time of his death, he was readying the release of the first new Shellac album in a decade, called To All Trains.

Albini was born in Pasadena to Gina and Frank Addison Albini. His father was a wildfire research scientist and the family moved many times before settling in Missoula, Montana.

Albini took up bass guitar (for one week) on hearing The Ramones’ first album and later immersed himself in the Chicago punk scene, contributing to local fanzines while studying journalism at Northwestern University. He started to take on informal engineering jobs with local bands and experimented with his own music, even though he later claimed “I have a voice like a harpooned whale and I cannot carry a tune.”

Big Black’s debut Lungs EP was a solo effort, before Albini recruited Jeff Pezzate and Santiago Durango to the line-up. The freshly constituted trio signed to Chicago indie label Touch and Go Records and released two albums, Atomizer (1986) and Songs About F***ing (1987), replete with dark lyrics on child abuse, fascist dictators, arson and pornography.

On disbanding Big Black in 1987, Albini formed Rapeman, named after a Japanese comic. He later regretted the choice of name, likening it to getting a bad tattoo, and copped to accusations of misogyny, racism and homophobia in his work, saying “I don’t expect any grace from anybody about that”.

Albini had no filter when criticising music and attitudes he disliked – including bands he had worked with.

He was not a fan of Nirvana, describing them as “REM with a fuzzbox” when he took on production of their 1993 album In Utero but wrote to the band suggesting they “bang a record out in a couple of days, with high quality but minimal ‘production’ and no interference from the front office bulletheads.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the time, Nirvana were the biggest rock band on the planet but, like Albini, Kurt Cobain was punk at heart. In the end, the “bulletheads” did intervene and the album was remixed post-production to make its raw aesthetic more commercially palatable.

Although Albini habitually worked with analogue equipment, he acknowledged that the rise in digital recording had democratised recording, with artists now capable of doing their own engineering.

When asked last year about how he would like his work to be regarded, he replied, “I don’t give a s***. I’m doing it, and that’s what matters to me… I was doing it yesterday, and I’m gonna do it tomorrow, and I’m gonna carry on doing it.”

He is survived by his wife, filmmaker Heather Whinna.

Obituaries

If you would like to submit an obituary (800-1000 words preferred, with jpeg image), contact [email protected]