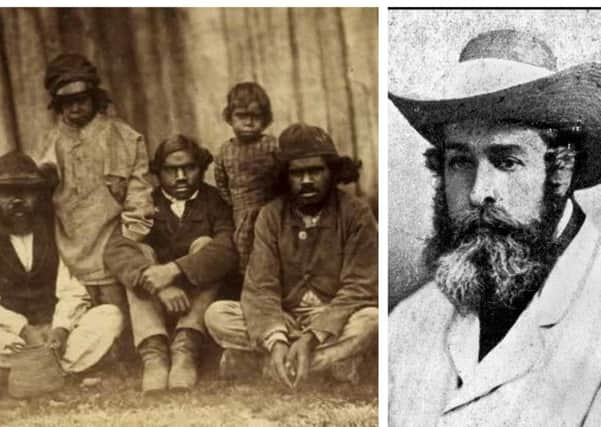

The Highlander who became a '˜champion' of Aboriginal people

Father McNab, from Morvern, who was ordained as a Catholic priest in 1845, is still revered in tribal tradition of the north west of Australia as a man who fought for the rights of its indigenous people as colonists took charge of large swathes of the country.

The priest, who served for a time in Airdre, North Lanarkshire, believed the only hope for the future of the indigenous population was to treat them as people deserving of property and human rights.

Advertisement

Hide AdHis beliefs took many years to manifest in any real change, which occurred long after his lifetime, but Father McNab stood for change at a time of widespread dispossession and frontier violence.

Killings of both settlers and Aboriginal people were rife, with the death toll including the massacre of at least 24 indigenous people by police at Cooktown in Queensland, a British colony from 1859 to 1901.

“McNab’s curious mixture of Celtic mysticism and Scottish common sense antagonized many...but his proposals for native welfare would, if adopted, have saved much agony,” the Australian Dictionary of National Biography said.

After arriving in Australia in 1867, Father McNab spent years working to secure a Catholic missionary - even personally visiting Rome to lobby for the post - but it was not until 1875 that he started work in Queensland.

He joined the Aboriginal Commission the following year to help assess the state of the population but the Scot feared the organisation was a limp facade for government inaction over the conflicts in the countryside.

The priest became instrumental in setting up new reserves set aside for Aboriginal people in New South Wales under the tenure of prime minster John Douglas, who was raised in Edinburgh.

Advertisement

Hide AdOne 2,130 acre reserve at Durundur was established after assurances were given to the Scot by local people that they would settle in the area, provided they had official endorsement,

For several years, McNab worked with around 200 people on the reserve selling stock and renting out a paddock for police horses, according to accounts.

Advertisement

Hide AdHowever, as documented in The Way We Civilise by Rosalind Kidd, the reserve was closed down in 1885 due to ‘white agitation’ against the community.

The speed at which the reserve was disbanded prompted Father McNab to lobby for the Aboriginal people’s rights to purchase land.

He argued: “Ownership would enhance Aboriginal conversion to the work ethic. When once they learn that they can possess property, the are willing to labour for its acquirements and wish to transmit it to their posterity.”

The killings at Cooktown halted any sense of progress in the conversation surrounding rights of Aboriginal people.

Father McNab resigned in disgust from the Aboriginal Commission over what he perceived to be a lame response to the atrocity and its failure to hold the government and police to account. Other resignations followed and the Commission collapsed.

As scrutiny failed, the reserves at Mackay, Bribie Island and Durunder were settled with Aboriginal people cut off from their hunting and fishing grounds and water.

Advertisement

Hide AdFather McNab wrote that the government was directly accountable for the continuing atrocities because it maintains a “steady army of native troopers under European officers for the protection of colonists and of their flocks, by the destruction of the Aborigines.”

The Scot left Queensland in 1882 amid growing resistance to his views. He ended up setting up a mission station in the remote north of the Kimberley region but age and illness was to bring and end to his work.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“According to Aboriginal tradition, McNab, tired and old, rode from Derby to Albany accompanied by one faithful Aborigine,” one account said,

He took sailed for Melbourne where he lived in a Jesuit house at Richmond and worked quietly as a parish priest until he died on 11 September 1896.