Trade mark clock counts down to Brexit

Brexit is coming and many of our household food and drink brands could soon be feeling the impacts in one particular area – trade marks. Of particular concern to trade mark holders in the food and drink sector is the latest version (March 2018) of the Draft Withdrawal Agreement (DWA) for leaving the European Union (EU) which outlines the relationship between the UK and EU during the transition period and beyond in relation to trade marks.

In most jurisdictions, including the EU and UK, the law requires the owner of a trade mark to put it to use within five years of its registration, the most obvious of uses being affixing the mark on products (there are other types of “uses”).

If the mark is not used within the five-year deadline, the mark is open to being revoked by third parties for non-use. This is a fair and logical legal provision, as a trader cannot “lock down” a mark if he has no intention of using it.

In its current format, the DWA states that the owner of a European Union Trade Mark (EUTM) registered before the end of the transition period shall become the owner of a “clone” UK Trade Mark (UKTM), ensuring continued protection in the UK after Brexit.

It also states that that these “clone” UKTMs cannot be revoked for non-use during the transition period.

However, after the transition period ends, they are stripped from the immunity from revocation, and as soon as the deadline to put them to use has run out, they become vulnerable to attack from third parties.

Therefore, a “clone” UKTM could be revoked for non-use as early as the day after the end of the transition period, that is on 1 January, 2021.

This is a serious issue that cannot be left until the last moment to resolve, and for companies that do not have a presence in the UK, speed in addressing this issue is still more of the essence.

In addition, the DWA states that during the transition period, the fate of the “clone” UKTM is linked to that of the “parent” EUTM.

If the EUTM is revoked (for whatever reason), so too is the clone. The immunity is therefore somewhat virtual if you consider that one only needs to successfully attack the EUTM to revoke both the EUTM and the UKTM.”

Protected geographical indications (PGIs) – for Scottish salmon, Arbroath smokies etc – are another related area of uncertainty for food and drink brands: the DWA provides for a similar process to trade marks, but these provisions have not even been agreed to at the negotiator level.

Moreover, the UK does not currently have its own domestic legislation regarding the protection of these rights.

However, as we keep being reminded, “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed”, so the DWA should not be considered as legally binding in any way towards the UK and EU until both have ratified the agreement in its totality.

Therefore, there is still a degree of “wait and see” involved in defining what will be finally agreed as regards trade marks, PGIs and other crucial areas.

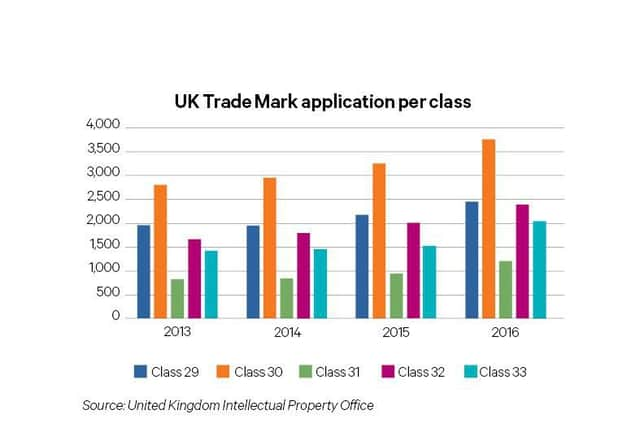

To quantify the importance of trade marks for the sector, one measure of this is the number of trade mark applications filed.

Since 2013, there has been a steady rise in the number of UKTM and EUTM applications for goods related to food and drink (in the related trade mark classes 29, 30, 31, 32 and 33).

Interestingly, of those, a sizeable number originate from applicants that are neither from the EU nor the UK, proving that these markets are still very much attractive for foreign direct investment in this sector.

A number of factors could be said to have influenced this growth, one of those surely being the emergence of new trends in consumer behaviour in relation to food and drink.

With consumers now leaning towards organic, allergen-free, vegan and responsibly sourced products, the industry as a whole has had to adapt by launching new products that meet these expectations. With new products come new trade marks. The fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) market is a highly competitive one where speed and accuracy are the key to success.

In terms of branding, the ability for companies to distinguish their products effectively from competing products is vital to consumer retention.

With the array of choice inundating the market, products with distinctive personalities are far more likely to become blockbusters.

The road to success is also conditional on a proactive branding strategy, which implies working hand in hand with trade mark attorneys during conception so as to avoid serious legal issues down the line.

One only has to look at the vast sums and the lengths to which industry leaders go to, to protect their brands, in order to understand their value and importance (for example, Nestlé litigated against Cadbury up to the Court of Justice of the European Union to protect the shape of the KitKat bar).

What is more, proactive branding can be a force multiplier for smaller businesses who do not have the same resources as sector giants, if they effectively leverage the goodwill associated with their brand.

With Brexit fast approaching (the transition period starts on 29 March), auditing the company’s intellectual property (IP) portfolio should be the first step in understanding its current positioning in this regard.

There are certain questions businesses need to ask themselves now:

- What are your current and prospective key geographical markets?

- Which are your key brands for which you cannot afford to lose protection?

- Where are these brands being used (within the legal definition of “use” of trade marks)?

Thankfully, there are a number of pre-emptive steps businesses can take in relation to their trade marks today, depending on their own individual circumstances:

- If the UK is a key market and you only hold an EUTM, filing an independent UKTM on top of the “clone” UKTM is of paramount importance as the latter can be indirectly revoked or invalidated, even during the transition period. Further, putting the marks to genuine use within the UK as soon as possible will be of equal importance, as use in the EU will only sustain the “clone” UKTM until the end of the transition period.

- If the UK and EU are both key markets, the same advice as above applies for the same reasons.

- If the EU is your key market, there isn’t much change other than future ownership of an identical “clone” UKTM. However, you should consider whether or not you may wish to expand to the UK in the future, in which case the same advice as above applies. Bear in mind that renewal fees in the UK are low and that this free trade mark should not be allowed to lapse.

- If you hold an international trade mark registration designating the EU, it should also initiate a subsequent designation of the UK.

- If the business holds both identical UK and EU trade marks and is considering expanding internationally, it should base its international application on the UKTM as a smaller territory of origin means a smaller risk of litigation against the base mark.

- For owners of PGIs, given that there may be an equivalent procedure to trade marks agreed, it may be possible to simply rely on the EU right being copied over to the UK. However, given the fact that this has not yet been agreed at negotiator level, precaution warrants registering it in the UK as and when such as scheme becomes available there.

Finally, it is recommended that all businesses with trade marks important to their commercial strategy take the opportunity, before the start of the transition period on 29 March, to speak with a trade mark attorney to discuss the best and most cost-effective strategy for safeguarding their brand assets.

Mike Vettese and Alain Godement are trade mark specialists at Murgitroyd, international patent and trade mark attorneys.

Protecting your brand

- Intellectual property (IP) – creative work which can be treated as either an asset or physical property. Intellectual property rights fall principally into four main areas: copyright, trade marks, design rights and patents.

- Intellectual Property Office (IPO) – the official government body responsible for intellectual property rights in the UK.

- Trade mark – a sign (eg a word or logo) capable of distinguishing the goods and services of one trader from another.

- Patent – a patent is granted by the government to the inventor, giving them the right to stop others, for a set period of time, from making, using or selling the invention without their permission.

- Copyright – the legal right that grants the creator of an original work exclusive rights for its use and distribution.

- Design rights – prevents someone else from copying your design and automatically protects it for ten years after it was first sold or 15 years after it was created, whichever is earliest.

- EU Trade Mark (EUTM) – a trade mark which is pending registration or has been registered in the European Union as a whole.

- Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) – a protection mark for products which are produced, processed or prepared in the geographical area you want to associate with it. The EU will only grant a product the PGI mark if they deem it to have a reputation, characteristics or qualities that are a result of the area you want to associate it with. Examples include Scottish Smoked Salmon, Scottish Farmed Salmon and Arbroath Smokies.

Don’t be innocent about your brands

Branding – just pick a name and start selling, right? Wrong. To illustrate the woes that can ensue from an ill-thought out branding strategy, we take a look at the example of an unfortunate vitamin manufacturer.

“Innocent Vitamins” came to the attention of well-known smoothie brand “Innocent Drinks” in 2011 when it started trading under the “Innocent” name in a font highly reminiscent of the smoothie company’s distinctive trade mark.

The intent to profit from the goodwill associated with the smoothie brand and from the confusion between the two marks was evident.

The reaction from Innocent Drinks was immediate and the owner of the competing product was politely asked to stop trading under that name, despite the fact that the vitamin pills had already been manufactured and sold in a number of high street supermarkets around the UK, resulting in the vitamin company having to abandon the name altogether, clearly incurring huge expense.

Contrast Innocent Drinks’ well thought-out branding and promotional strategy which included registering trade marks for its products and thereafter successfully marketing those trademarked products – resulting in the company founded in 1998 by a trio of Cambridge graduates now being valued at in the region of £320 million.

The risk in not getting professional advice on trade marks from inception of a product isn’t only litigation, but also the very real possibility of having to remove infringing products from the shelves.

Contacting a trade mark attorney early on in a product’s development can save time, expense and worry, and help to underpin branding strategies by providing legal certainty.

For more information, visit www.murgitroyd.com

This article is taken from The Scotsman's Annual Food & Drink Supplement which can be read in full here.