Data Capital: Can't see the data for the trees

Whenever he drives to Glen Coe to indulge his long-running passion for hillwalking and rock climbing, Charles Kennelly feels a wee twinge of pride gazing upon the forests growing on the hillsides surrounding Loch Lubnaig. “I had a small role in helping that happen,” he smiles.

For the past 26 years, Kennelly and his colleagues at technology company Esri UK have been working with the Forestry Commission –and, since 2019, one of its successors, Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS) – to change the way that foresters use data to manage trees.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Forestry Commission was created in 1919 in the aftermath of the First World War to replace the woodlands that had been decimated during the war effort to provide timber for the front lines.

Today, FLS manages 640,000 hectares of forest and land, amounting to around 9 per cent of Scotland’s surface area. Growing trees for timber is no longer its sole purpose, with its remit now widened to give the public access to forests for exercise and recreation, increase our nation’s biodiversity by managing woodlands for wildlife, and help to mitigate against the worst effects of global warming through soaking up rainwater to help prevent flooding.

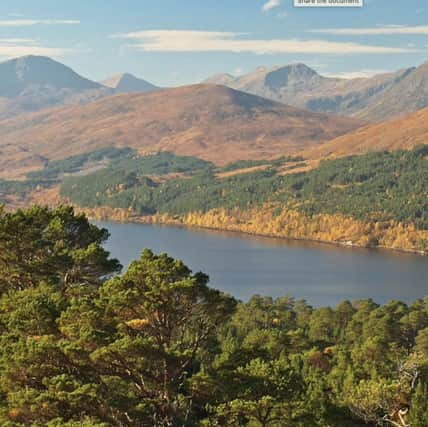

“A lot of Scotland’s forests were planted in the 1970s as monocultures – Sitka spruce – with straight edges,” explains Kennelly, who has worked on the project since it began and is now Esri’s group chief technology officer. “The forests that have emerged over the past 20 or 30 years are more diverse – their colours change over the course of the year because they contain more deciduous trees, not just the blue-green of Sitka spruce.

“Foresters can see whether something is sympathetic to the ridgeline, whereas in the past it was a rectangle. So now when you look at the forests as you drive towards Glen Coe, you will see they follow the natural features much more. They feel like part of the landscape more than they did.

“They just look better, in my view; they feel more natural. That’s the thing that I’m proud of – we’ve helped make that change.”

Back when Kennelly and his colleagues began working with the Forestry Commission in 1997, it took eight or nine months to produce a production forecast for the average forest, matching up the available trees to how much timber could be harvested. Foresters would go out into the field to collect information and then experts back in the central office would transcribe the data.

“The software only took three or four hours to produce the forecast, but what took so long was dealing with the errors because the data wasn’t consistent,” Kennelly remembers. “So, it became an exercise in how do you stop people making mistakes with data.”

The solution was to check the data was accurate at the point of entry, rather than later in the process. For example, if someone tried to enter a tree’s co-ordinates as being in the middle of the North Sea rather than on dry land then the system could reject that data at the point of entry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The person making the edit, like “these trees have blown over”, was the forester in the field. But the person transcribing the effort was an expert in mapping. And I needed the forester to do it, which took out a huge amount of work and also removed a lot of duplication of information.”

By restricting the changes that foresters could make to a map of the forest to just four functions – modifying boundaries, splitting areas, combining areas, and changing the attributes of an area, such as which trees were growing there – Esri could improve the quality of the data being collected.

Speeding up the rate at which production forecasts could be produced meant that the forestry bodies could then test different options – what would happen if we left these trees to grow for a further five years. or what would happen if we harvested them early?

As well as conventional maps, Esri also developed 3D models, allowing foresters to picture what a piece of woodland would look like in the future. In popular tourist areas, the tool allows FLS to judge whether planting a forest in a certain location would spoil the view from a neighbouring hotel.

Now, FLS staff working out in the field can access a program called Forester (built on Esri’s Arc Geographic Information System, or GIS), on their mobile phones and input data straightaway.

“One of the people working for the Forestry Commission said to me that the introduction of Forester and the way it keeps data up-to-date and allows them to do this option testing was the biggest change to forestry since mechanisation – which is quite a powerful statement,” adds Kennelly.

Images and other data gathered by drones is now allowing Esri to harness information about the health of woodlands, down to the level of individual trees and the soil beneath them. The next step will be to incorporate machine learning into Forester, allowing the system to not only test different options for planting, but also to analyse those options itself and come up with recommendations.

“It’s hard to overestimate the importance of GIS in all our activities,” says Colin Hossack, strategic planning manager at FLS. “Before we started working with GIS and Esri, we used to manage our inventory using these big maps that hung in a cabinet and once a year we’d get this big database printed off.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWorking in remote areas, FLS staff can download the maps they need to their phones, update the information, and then synchronise it when they get a signal again, or get back to their office. Being able to use data and model different options is a key part of the agency’s response to the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss.

“Using GIS is absolutely critical in our response to forest fires or storms on the scale of Arwen,” adds Hossack. “Having GIS means we can take a strategic approach to how we respond to situations and allows us to share data with our partners as part of the wider emergency response.”

Forestry in figures

◆ 9 per cent of Scotland’s land is managed by Forestry & Land Scotland (FLS)

◆ 640,000 hectares of land are managed by FLS

◆ 470,000 hectares of woodland are managed by FLS

◆ One third of Scotland’s forests are managed by FLS

◆ Three million of tonnes of timber are produced by FLS each year

◆ 10.6 million public visits are managed by FLS each year

◆ 1,000 species live on land managed by FLS

◆ 172 protected species live on land managed by FLS

◆ 16,000 archaeological features are recorded on land managed by FLS

◆ 600,000 homes could be powered by renewable energy from land managed by FLS

Source: Forestry and Land Scotland